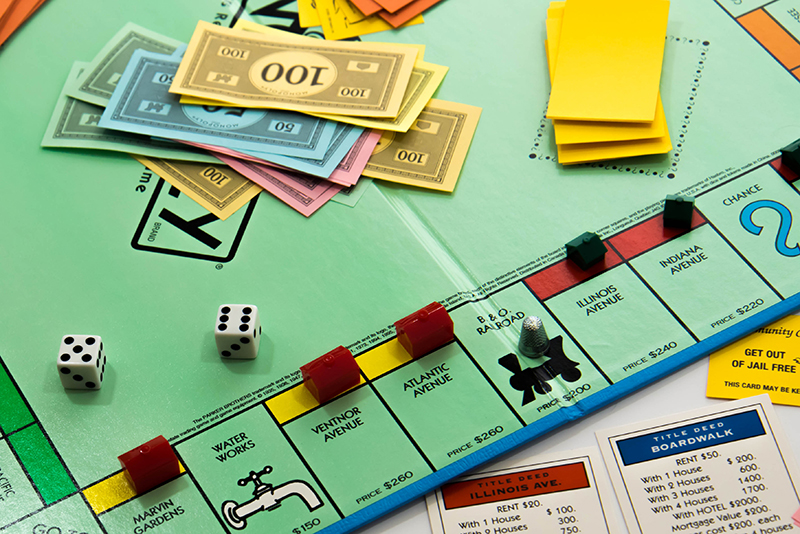

Supply selection is more than a roll of the dice

What influences supply chain managers to make one decision over another and take risks in the purchasing process? Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management Thomas Kull delves into the factors that affect decision-making in his new research.

Risk is a tricky business. Companies roll the dice and sometimes they hit the market jackpot. In other cases, they fold with a miserable, miscalculated loss. Remember New Coke? How about Crystal Pepsi?

While those products were colossal flops, the poorly conceived brand concepts didn’t sink the beverage giants’ core business. Yet other types of risks in business are more dynamic and can be acute, decision-making gambles that have long-term consequences.

In the supply chain arena, for example, the consistent movement of goods — or the lack thereof — is a daily game of chance for selection managers who play a strategic role in a company’s success amid a constant environment of internal and external uncertainty.

Motivating supply manager selection

What influences supply chain managers to make one decision over another and take risks in the purchasing process? Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management Thomas Kull delved into the factors that affect supply chain decision-making in his research study titled, “Supplier Selection Behavior under Uncertainty: Contextual and Cognitive Effects on Risk Perception and Choice.”

Existing literature outlines many of the analytical attributes that drive supply chain preferences, but the psychological aspects that lead to managerial decision-making aren't as well explored, according to Kull.

“I wanted to know how managers got themselves there, to begin with; how they arrived at risk in the first place and under what circumstances they took a risk,” he says. “Sometimes it makes sense for managers to take a risk. The question is, what motives managers to be more or less risky?”

To expose both the contextual (i.e., performance pay) and cognitive (i.e, personal judgment) circumstances that influence supplier selection, Kull conducted a controlled experiment with 119 practicing managers with supply chain experience in the manufacturing, health care, and service industries across the United States.

The study included an anonymous, online questionnaire modeled after a classic behavioral methodology in which managers had to choose between two hypothetical scenarios, one that produced a higher performance result with unexpected risks versus a run-of-the-mill choice with highly reliable outcomes.

An element of risk perception is always at play in decision-making whether a person is on the job or deciding on a place to eat, according to Kull, who compares the line of questioning used in his study to picking a restaurant.

“The first restaurant is a place you have been to before and delivers meals on time, but the food is not terribly tasty. The second is a new restaurant with positive and negative reviews. It seems like an interesting choice but things could go badly,” he says. “If you choose the second restaurant, you’ve decided the potential upside outweighs the potential downside.”

To risk or not to risk?

A growling stomach probably forces many to take a food risk, but one significant finding of the research conducted by Kull and his colleagues is that managers are too conservative in their perception of risk, especially when it comes to selecting products that give companies an edge over their competitors.

Based on study results, if a purchase involves an important or difficult degree of a sourcing category, 73.5 percent of managers have a tendency to be more risk-averse and choose suppliers known to have certain outcomes but with lower-expected payoffs.

“We discovered that supply chain managers tend to embed their risks in products that are not strategic,” explains Kull. “When faced with choosing a product that is strategic — or core — to their operations, they defaulted to a vanilla, or inferior, product.”

The problem with taking the path less risky in supplier selection is that it often comes at the expense of creating opportunities for innovation and reward, which sabotages a company’s shot at being highly competitive and successful. “If you are trying to be an innovative company, it means you have to accept certain levels of risk,” says Kull.

An obvious, hidden element

The study also revealed an unexpected but intriguing discovery based on a psychometric analysis that aimed to detect supply chain managers’ latent risk propensity — or their bias to accept or not accept risks.

Kull and his research team learned that among the managers polled, a bias for latent decision-making wasn’t exactly a suppressed event as previously understood.

“Contrary to what literature has presented in the past, which suggests if you have a latent risk propensity bias you will be blind toward risk, our study found those with latent risk propensity are fully aware of the risks they are taking,” Kull says.

In terms of supplier selection, a manager’s known willingness for risk propensity could influence how he makes decisions regardless of how he perceives the inherent risks. “It’s like extreme sports athletes,” adds Kull. “They know the risks they are about to take — and they take them.”

Blinded by bias

On the other hand, some risk occurs due to a blind spot caused by the lure of a personal incentive, which has both advantages and disadvantages to an organization.

Kull evaluated how performance factors, such as contingent pay, influence a manager’s propensity for risk and decision-making. Results from this study indicate that if managers expect to receive stock options or a bonus, for example, because a supplier selection produced a company cost-savings, it blurs their perspective on being able to handle a situation, such as obtaining rush orders during supply disruptions or negotiating supplier concessions if costs increase.

In other words, a higher percentage of contingent pay is associated with lower perceived risk because managers operate on the allusion they are able to mitigate the consequences of their decision.

“It induces a false sense of control over a situation and, in turn, affects the amount of risk a manager takes,” says Kull. “The presence of a contingent pay structure caused the study participants to be riskier because it blinded them to certain risks."

The finding suggests compensation schemes are a double-edged sword. While performance incentives generate increased employee benefits and possible company rewards, according to Kull, the downside is they can cloud managers’ perception of potential risks and desensitize them to risky behaviors.

The future of supply selection analysis

While focusing on the psychological aspects that affect supply chain decision-making and risk is a relatively new research pursuit, Kull believes his study challenges traditional assumptions that supply managers act as agents of a firm without personal biases or preferences influencing their choice.

In addition, the research results not only provide a practical application for supply chain managers today but also contributes a valid theoretical framework for further investigation into the conditions under which buyers make supplier selections during uncertainty.

The bottom line

- Know what makes your employees tick. Professor Kull recommends supply chain managers understand the personalities and risk profiles of their supply staff. What factors motivate them to take — or not — take risks? Are they making decisions based on personal bias rather than the needs of the organization? If managers have a grasp on their team members’ mindset for decision-making, risks will be mitigated and outcomes will be more consistent in the procurement process.

- Professor Kull also advises higher-ups concerned with upstream supply processes to speak with chief procurement officers and general supply chain managers about the commodity products that their employees are buying, which are less important to the core business. Instead, have them focus on making riskier, strategic selections to gain a competitive edge with greater results.

- If chief procurement officers are challenged by supply managers who are having a difficult time being innovative, it is critical to look at both the positive and negative factors that affect innovation and figure out ways to introduce incentives. Sometimes that means establishing contingent pay or changing their pay structure so more risks are taken in the pursuit of long-term business success.

Latest news

- AI + human intelligence = new skillsets for SCM leaders

Organizations that adopt "human-in-the-loop" AI systems are more likely to succeed than those…

- Former federal economist joins ASU to advance real estate research

After nearly a decade in government, Robert Martin joins the W. P.

- A look at the downside to employee loyalty

While unpaid overtime and skipped breaks might be seen as morally acceptable or acts of…